Whether you manage a commercial facility, apartment complex, school, or subdivision, you know that detention ponds are a fact of life. If you maintain a detention pond, you also know how difficult that can be.

For a pond that was designed and constructed correctly, however, maintenance isn’t all that difficult; basically only requiring monthly mowing and fertilizer twice a year.

But what about those detention ponds that won’t dry out between rain events? The reasons detention ponds hold water are varied and numerous, but more often than not, it is a result of improper design and/or construction.

It All Starts With The Survey

The first step in the construction process is to establish the elevations of both the property and the receiving storm sewer system. That may be a roadside ditch, underground storm sewer pipe, creek, stream, or bayou.

The first step in the construction process is to establish the elevations of both the property and the receiving storm sewer system. That may be a roadside ditch, underground storm sewer pipe, creek, stream, or bayou.

Regardless of the type, the receiving system needs to be surveyed to ascertain how deep we can dig the pond, as it will drain to that receiving drainage.

We know water flows downstream, so we have to be mindful of the receiving system’s flow line (bottom) and whether or not there is standing water in it. Unfortunately, many of our public drainage systems hold water due to blockages, sediment buildup, or lack of maintenance.

These static water levels rise and fall with rain events and seasonal changes, meaning this elevation is constantly in flux. Surveyors typically provide both the floor and static water levels. But today’s water level may be artificially high due to recent rains or artificially low from drought and summer heat.

So as you can see, finding the lowest point that we can safely discharge to without backing water up into the pond is a moving target. And in the case of artificially low water levels, when levels rise and stabilize, you may find several inches of water backed up into the detention pond.

Now The Engineer Needs To Make Some Choices

With survey data in hand, the civil engineer will design the detention pond with the proper grade to drain stormwater to the outfall pipe. They will then set that pipe above the static water line or flow line to allow the pond to drain dry between rain events.

Now, in a perfect world the pond floor would be graded at 2% to 5%. Meaning 2 13/32 to 6 inches for every 10 feet of length.

So if we had a 100 ft. long floor, we’re talking 2 to 5 ft. of fall. Detention ponds all have a required volume based on the impervious acreage of the property; therefore, if we employed these grades, the pond would have to be larger from side to side to accommodate the volume lost with a 2-5 ft grade.

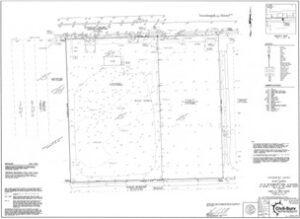

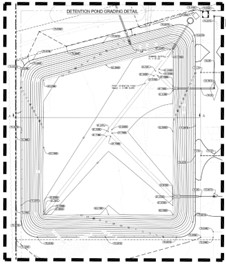

This is a typical detention pond design. The pond grade is .1%. This equates to 1.2 inches/100ft.

This results in a loss of valuable land, meaning less usable, income-generating space. A scenario no developer would accept without a fight. In the real world, we see grades that are flat from .2% to .5%.

This means

The photo and drawing above show a .5% grade (6 inches of fall per 100 ft.. As you can see the bottom is always soggy and can only be mowed by hand, adding to the monthly mowing cost.

for every 100 ft., we are falling 2 13/32 to 6 inches. So now we’re asking the dirt contractor to grade 100 ft. of pond floor to less than 3 inches.

And while that isn’t impossible, it leaves absolutely no room for error.

The Reason? Pressure

Civil engineers are constantly at odds with developers in the design process. Why, you might ask. It’s simple.

Civil engineers have several years of training in properly designing systems, understanding that system failures are inevitable without all of the proper design parameters in place.

So it stands to reason that engineers are less interested in the cost and more interested in providing sustainable solutions that limit or reduce the operation and maintenance budget for ownership.

On the other hand, developers, by nature, are more focused on the numbers; always looking for ways to shave unnecessary costs from the budget. The problem with this approach is two pronged.

First, it assumes that this exercise of budget crushing hasn’t happened umpteen times already. When in reality the budget has been beaten with a stick until it’s bloody and bruised, so anything we remove at this point is probably necessary.

Additionally, developers are less interested in the operation and maintenance than they are with the immediate challenge of building on-time and under budget. So you can see that these two are often at odds.

And unfortunately, even at the behest of the engineer, since the developer pays the bills, he always wins.

An Example

Let me give you a real-world scenario to help you understand the mindset of developers. A few years ago, I was asked by one of my customers to take a look at a rather large detention pond that was full of cattails (Typha).

Let me give you a real-world scenario to help you understand the mindset of developers. A few years ago, I was asked by one of my customers to take a look at a rather large detention pond that was full of cattails (Typha).

I happened to know the civil engineer of record who told me that he walked the pond upon completion of construction, claiming that it was totally dry at that time.

So why did the pond constantly hold 1-2 ft. of water just a few years later? A mystery, to be sure.

While talking to the engineer, it was revealed that in the developer’s effort to show his superiors that he was an “out of the box” thinker, he decided to save on disposal costs for the vegetation on the property. (this was raw, forested land) He would over-excavate the pond, bury the mulched trees and shrubs in the floor, and cover it with soil to finished grade.

As a bonus, this provided him extra soil for the building pad, an additional cost savings. What he didn’t consider was that as the vegetation decomposes, it compacts, resulting in a slowly sinking pond floor.

Of course, by the time this happened (several years later), the developer’s rep was long gone, and everyone thinks he did a great job delivering on time and under budget. But in this case, the property owner is a REIT with a development and management team, meaning the cost for repairs came from the same company that saved all of that money on construction!

Because the cost to add that dirt back to the floor was too extreme, the best we could do was create a wet 3×3 ft pilot channel along the length of the floor to contain most of the water. We used the soil from the channel to build the floor back up to drain into that channel. The channel will likely silt in the next 10-20 years, and that work will need to be redone.

And while somewhat contained, we’re still left with standing water and the problems associated with it. Do you think the developer would think his ideas were great if he could see the results? I think not.

“Kicking The Can” Down The Road

Defying or ignoring this reality is just delaying the inevitable and deferring ownership of the problem to management. But if you’re reading this because you have a pond holding water, you already knew that.

If your company builds, owns, and manages its properties, this may be an excellent opportunity for development and management to collaborate to avoid the problem in the first place. But more than likely, you’re on your own trying to come up with a solution for a wetlands area that invites rodents, snakes, mosquitoes, and other undesirable critters to your property.

This can result in tenants moving out and makes your property less marketable.

What’s The Solution?

The pond floor grade is not always the problem. Sometimes the solution is as simple as a clog in the drainpipe that has gone unnoticed. Or (in the case of lift stations), the floats in the lift station may need to be lowered.

Unfortunately, there is no “one size fits all” solution, and a site visit by qualified personnel with years of experience in this sort of troubleshooting is always necessary to properly diagnose the problem. If the pond floor does need to be raised, the costs can quickly skyrocket, so this is always the last resort.

Of course, as always, we are committed to providing cost-effective solutions that fit into your budget and risk tolerance.

If you would like to learn more about how we can help you with your specific needs please feel free to contact us for a complimentary site assessment. Give us a call at (832) 554-6654 or email us at info@swpgrp.com